|

Cleator Moor was a

windy stretch of moorland until the 1780s when it was realised that rich

deposits of haematite or iron ore lay not far below the surface. The following

century saw something akin to a Klondike rush as the iron ore was exploited

in ever growing quantities. So great was the influx of workers from Ireland,

via the Irish trade port of Whitehaven, that even to this day the area

has a high proportion of Roman Catholics and the nickname of Little Ireland.

As the ironmasters of the Industrial Revolution demanded the high quality

ore the area, after 1850 became criss-crossed by railway lines ..all now

disused and turned into cycleways

for the leisured classes.

One of the earliest

iron ore workings in the area was at Langhorn on the limestone escarpment

above Egremont. This was worked by monks in the 12th century and in the

17th century.

In 1753 the Crowgarth

mine started with capital raised by Whitehaven merchants in the Virginian

tobacco trade. The owner of a large bacon curing business in the area,

Jonas Lindow then speculated on the iron ore deposits, his family became

wealthy as the iron trade boomed. At this stage the ore was shipped to

Scotland and South Wales furnaces from the port of Whitehaven. The mines

grew and grew as more ore was discovered. In 1870 the Crowgarth mines

were raising 42,000 tonnes. The town developed its rows of terraced houses

for the growing population of miners. The sheets of ore were followed

by the miners and digging got closer and closer to the surface. Eventually

homes started cracking up from subsidence and miners underground could

hear the town clock chime as they worked underground. As an added bonus

the Montreal mine even had coal and iron coming up the same pit shaft.

The deposits of limestone in the area meant that the building of iron

works followed.

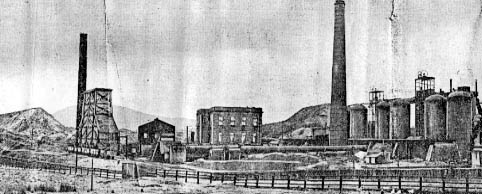

See the illustration of Cleator Moor’s

iron works with its furnaces. The picture was dated 1934 as the works

stood idle awaiting demolition. Output at Montreal rose to 265,678 tons

by 1677. There were even plans for a new ironworks at Whitehaven, but

this plan was dropped after Lord Lonsdale refused to give his support.

The iron ore deposits were chased south into Dalzell’s Moor Row district

where mines such as Montreal 8,10 and 11 pits used the influx of Cornish

tin miners to carry out the work. Crossfield, Jacktrees and Todholes mines

were other highly profitable pits that shared in the booming industry.

But deposits were thinning and after a last minute surge in demand for

the First World War the iron mining industry was set on a relentless decline

through the 1920s and 30s. The only remaining iron mining operation in

West Cumbria is that at Florence Mine, Egremont. See the illustration of Cleator Moor’s

iron works with its furnaces. The picture was dated 1934 as the works

stood idle awaiting demolition. Output at Montreal rose to 265,678 tons

by 1677. There were even plans for a new ironworks at Whitehaven, but

this plan was dropped after Lord Lonsdale refused to give his support.

The iron ore deposits were chased south into Dalzell’s Moor Row district

where mines such as Montreal 8,10 and 11 pits used the influx of Cornish

tin miners to carry out the work. Crossfield, Jacktrees and Todholes mines

were other highly profitable pits that shared in the booming industry.

But deposits were thinning and after a last minute surge in demand for

the First World War the iron mining industry was set on a relentless decline

through the 1920s and 30s. The only remaining iron mining operation in

West Cumbria is that at Florence Mine, Egremont.

An excellent illustrated book on this fascinating area is The Red Hills,

by Dave Kelly, published Red Earth, Ulverston ISBN 0 9512946 7 9.

Cleator Moor also suffered from a sectarian divide arising from the influx

of Irish workers..matters reached a low point in the so called Murphy

riots. The notorious anti-Catholic William Murphy was attacked by 300

Cleator Moor iron-ore miners at Whitehaven in 1871 At the time of the

Irish Potatoe Famine Jobs were plentiful and all of the West Cumbrian

towns such as Whitehaven and Workington as well as large villages like

Cleator Moor developed sizeable Irish populations with the mix of Catholics

and Protestants providing potential for sectarian quarrels.Murphy, a notorious

anti-Catholic came to Whitehaven in April 1871 the Magistrates decided

to allow him to speak in the Oddfellows Hall only for him to be attacked

by 300 well-drilled iron-ore miners from Cleator Moor. The police, caught

unawares and hopelessly outnumbered, could do little for him and before

a rescue could be effected Murphy was horribly beaten. It was some weeks

before he recovered sufficiently to face his attackers in court. As consequence

five men were given 12 months with hard labour and two got three months.

Murphy came back to the town in December, despite the entreaties of the

local magistrates, but events passed off relatively smoothly. In March

1872 died, Birmingham surgeons claimed, because of the lingering effects

of the savage assault dished out by those Cleator Moor miners. The Press

was horrified that a man could die for his views and there followed an

Orange revival in Cumbria. Until recently Orange parades were a regular

feature in Whitehaven and Workington.

|

|